The truth about finding a cure for cancer

Category : Tell us your Story | Sub Category : Tell us your Story Posted on 2025-10-14 12:30:29

The truth about finding a cure for cancer

When people say, “I want to cure cancer,” it sounds noble — but it’s actually a drastic oversimplification of what cancer really is. Cancer isn’t a single disease. It’s a term that covers hundreds, maybe thousands, of distinct conditions that all share one thing in common: uncontrolled cell growth.

So asking “how do we cure cancer?” is a bit like asking “how do we cure coughing?” Coughing isn’t a disease in itself; it’s a symptom caused by different underlying problems. Cancer works the same way — it’s the result of many different cellular and genetic failures.

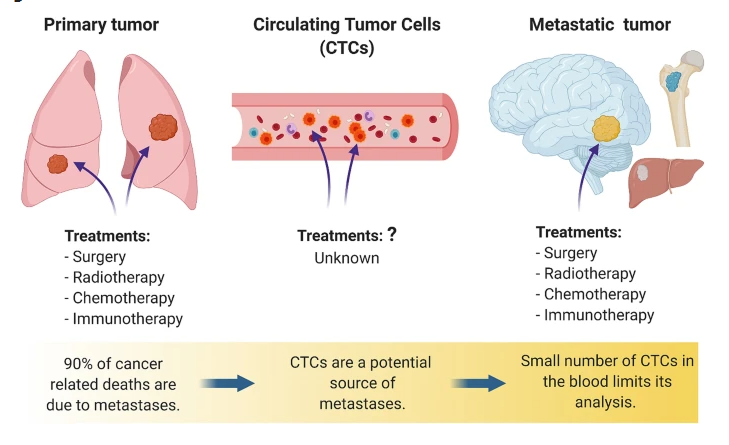

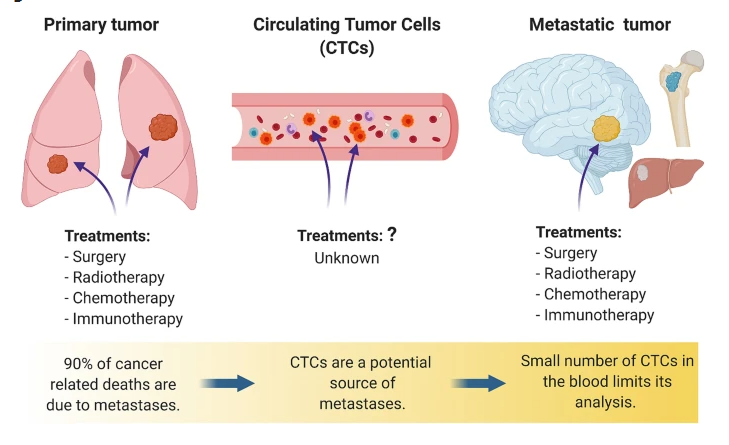

At its core, cancer starts when genetic mutations cause cells to grow and divide uncontrollably. But that’s only part of the story. Tumor cells also learn to evade the immune system, avoid programmed cell death (apoptosis), produce their own growth and blood vessel signals, and even break down nearby tissues to spread elsewhere in the body (metastasis). And we’re still discovering new ways they manage to survive.

Some cancers are curable. For example, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, stage 1 melanoma, and squamous cell carcinoma often respond so well to surgery or drug therapy that patients go on to live full lives, dying years later of something completely unrelated. That’s what doctors mean by a “cure.”

Other cancers are better described as manageable. Conditions like follicular lymphoma or certain slow-growing prostate cancers progress so gradually that doctors sometimes recommend “watchful waiting” instead of immediate treatment.

What’s fascinating is how treatment has become more targeted. We now know that cancers with different genetic mutations behave like entirely different diseases — even if they start in the same organ.

Take breast cancer, for instance:

- If it expresses estrogen receptors (ER+), it can respond to drugs like tamoxifen.

- If it’s HER2-positive, therapies like trastuzumab (Herceptin) are used.

It’s the same with lung cancer — tumors with EGFR mutations respond to erlotinib or afatinib, while those with ALK mutations respond to crizotinib or ceritinib.

This shift shows why a single “cure for cancer” is unlikely. Each type, and even each patient’s version of cancer, can behave differently. The future of cancer treatment lies in precision medicine — therapies designed for specific mutations, cell types, and individuals.

There’s a huge amount of promising research happening — from immunotherapy and targeted drugs to gene editing and personalized vaccines. The more we learn, the better we get at turning deadly cancers into curable or manageable ones.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH

Categories

Recent News

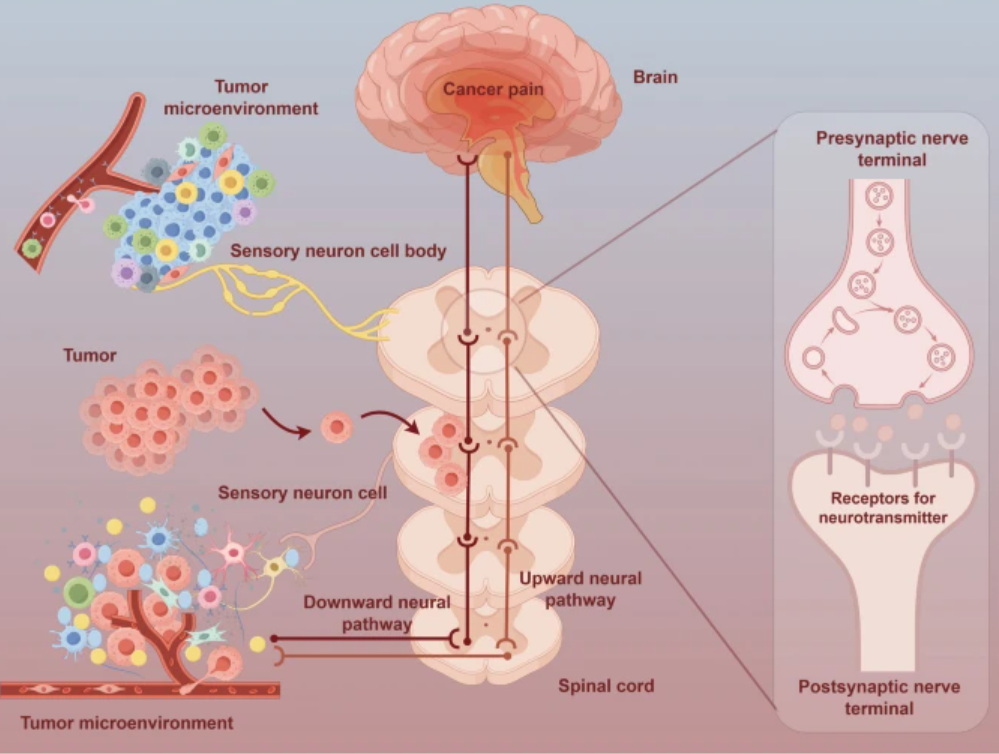

- Cancer Pain Medications

- Gastric Cancer (Stomach Cancer)

- New Discovery Links Mitochondrial DNA to Immunotherapy Success in Cancer Treatment

- John’s Journey: Healing Through Lifestyle and Natural Remedies

- The truth about finding a cure for cancer

- Federal Government Commissions Three Oncology Centres to Strengthen Cancer Care in Nigeria

- Nigeria Advances National Cancer Control Efforts

- Nigeria’s Biggest Cancer Awareness Walk by Mukhtasar M. Alkali

READ MORE

2 months ago Category : Tell us your Story

Cancer Pain Medications

Read More →2 months ago Category : Gastric Cancer

Gastric Cancer (Stomach Cancer)

Read More →3 months ago Category : Colorectal Cancer

New Discovery Links Mitochondrial DNA to Immunotherapy Success in Cancer Treatment

Read More →3 months ago Category : Tell us your Story